In part 1 of this series, I discussed how the IT landscape is changing, and that staying current means getting outside of your comfort zone and spending time experimenting with unfamiliar technology. In this post, we are going to take a look at Vagrant as a means of rapidly creating development and test environments so that you can skip the drudgery of installing operating systems and focus on the things that really matter.

Vagrant?

Vagrant is an open source project created by HashiCorp designed to create lightweight, reproducible development environments. The idea is that you can create an environment that mirrors (or is at least close to) production and hand it out to your developers by only sharing a handful of text files.

Overview

Vagrant works by abstracting away configuration of the virtual machine and hypervisor and storing relevant settings inside of a single configuration file. Rather than interacting with the hypervisor directly, you use the vagrant command to control the virtual machine(s) that you’re working with.

Each vagrant project should have its own folder. At a minimum, the folder contains a Vagrantfile, which contains a reference to the box you’re using and any VM or provisioning configuration. The folder should also contain any other files you want to be shared with the VM such as any script. By default, the entire project folder will be mounted inside of the VM at either /vagrant or c:\vagrant (if you’re running on Windows) and are available to processes running inside the virtual machine.

Choosing a Hypervisor

Vagrant has built-in support for VirtualBox, Hyper-V, and Docker out of the box, and has support for other types of virtual machines such as AWS and VMWare by using its provider system.

Prior to discovering Vagrant, I was using Hyper-V as my default hypervisor. After tinkering a bit, I switched to VirtualBox. Here is why:

- VirtualBox is Vagrant’s default provider, so all features are supported.

- There are many more pre-built boxes available with VirtualBox.

- Vagrant can use VirtualBox’s built-in shared folders to mount the project folder inside the VM, and will “just work” whether you’re on Windows, Mac, or Linux. With Hyper-V, you’re probably going to end up using SMB shared folders, which while faster than VirtualBox shared folders aren’t supported on non-Windows hosts, and require creating a share on the host workstation.

- I use a laptop with a high DPI display, and was occasionally frustrated when working on the console of a VM that didn’t support display scaling. VirtualBox fixes this issue for me. In general, VirtualBox had improved tremendously since I last tried it many years ago, and I was pleasantly surprised.

Because you can only have one hypervisor running at a time, if you want to try VirtualBox you’ll need to disable Hyper-V if you have it running. If you want to be able to go back and forth, you can create a boot menu to select between a Hyper-V and non-Hyper-V profile. Scott Hansleman has a nice blog on this here.

Choosing an Image

Vagrant hosts many images (boxes) on their Atlas service. As you expect, you’ll find many flavors of Linux, but will also find boxes built with 180-day evaluation copies of Windows. Because environments created with Vagrant can be destroyed and recreated, evaluation copies of Windows are a perfect fit.

Note: The evaluation period of a Windows image starts when it’s initially created, not when you first spin it up in Vagrant. Because of this, it’s best to ensure you choose an image that is updated frequently, or to learn how to build them yourself with Packer. For more on this, check out this awesome blog by Matt Wrock, or Chef’s Bento repository where they keep numerous Packer templates.

Some boxes support a single provider, while others support multiple. Either way, each Vagrant box on Atlas uses a USER/BOX naming schema.

Here are a few examples:

- ubuntu/xenial64 - Ubuntu 16.04, LTS

- ubuntu/trusty64 - Ubuntu 14.04, LTS

- mwrock/Windows2012R2 - Windows 2012 R2, Minimized

Deploying a VM with Vagrant

At this point, I’m sure you’re quite done reading about Vagrant and are ready to try actually using it. Because I hail from a primarily Windows background, we are going to spin up a Windows Server 2012 R2 machine.

Note: The image we are using has been minimized; all optional features have been removed and will be installed via features on demand. While this speeds up the initial download and works well for most things, there are some server roles that won’t install this way. Additionally, server roles you consistently use will have to be downloaded every time you instantiate a new VM and install the feature. Because of this, when you start your own project, it may make sense to create your own image that’s customized to your needs with the roles you require baked in.

Prerequisites

To follow along, you’ll need the following:

- A machine with enough RAM to run your OS plus the VM, and enough disk space to store the images you’re working with.

- VirtualBox downloaded and installed.

- Vagrant downloaded and installed.

If you’re on Windows, you’ll want a copy of ssh.exe in your path somewhere when working with *nix systems. It won’t matter much for this tutorial, so you can take care of this later if you’d like. If you’re reading this and looking at using Vagrant, there is a good chance you’re also using Git. If so, you can just add the included copy of ssh.exe to your path. A quick Google search says that you can use Putty, though I haven’t tried it. There is a blog on this here that looks like it should work. Me? I’m just going to stick ssh.exe in my path.

I’ll be performing these steps in Windows 10 at a PowerShell prompt, but it should work equally well on a Mac or in Linux.

You may notice in the examples that my command prompt looks a bit different from yours. This is because I’m using Cmder instead of the native Windows PowerShell prompt. It supports more colors than the native command prompt (something which is nice when using tools like Vagrant that are ported from an environment that has a 256 color command prompt) and because it adds a visual queue as to when I’m working inside or outside of the VM. In any of the examples, if the line starts with a

λI’m working on my native OS, and not inside the VM.

Vagrant Up!

Let’s start by creating a directory anywhere on your machine. First change to a working directory somewhere, then create a new folder to house our vagrant project and change to that directory.

I’m going to use c:\vagrantdemo for demonstration purposes.

md c:\vagrantdemo

cd c:\vagrantdemo

You should now be in a new, empty directory. Let’s create our first vagrant file. We are going to base this on Matt Wrock’s minimal Windows image: mwrock/Windows2012R2. To create the file, type:

vagrant init "mwrock/Windows2012R2"

You should see a message saying that a vagrant file has been placed in the directory. If we take a look inside the file, we will see that it’s mostly comments. If we ignore all of the comments and examples (everything starting with a #), we are left with three relevant lines:

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "mwrock/Windows2012R2"

end

Those few lines are enough to get us off the ground! The Vagrantfile is written in Ruby, but the syntax is easy enough to deal with even if you don’t know the language. We’ll dig more into other options later on.

Time to bring up a machine! From inside the working directory, type:

vagrant up

Vagrant will check your local store of downloaded boxes. If it finds the box specified in the Vagrantfile, then it’ll deploy it from there. Otherwise, it’ll pull it down from HashiCorp. After downloading, the image will be booted. This particular image has had sysprep run on it, so it’ll actually run through the Windows installation process. While installing Windows only takes a few minutes, the image is a few gigabytes in size (despite having many features removed), so this is a good time to make a sandwich or walk the dog. You should see a progress indicator with an ETA.

C:\vagrantdemo

λ vagrant up

Bringing machine 'default' up with 'virtualbox' provider...

==> default: Box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2' could not be found. Attempting to find and install...

default: Box Provider: virtualbox

default: Box Version: >= 0

==> default: Loading metadata for box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2'

default: URL: https://atlas.hashicorp.com/mwrock/Windows2012R2

==> default: Adding box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2' (v0.5.3) for provider: virtualbox

default: Downloading: https://atlas.hashicorp.com/mwrock/boxes/Windows2012R2/versions/0.5.3/providers/virtualbox.box default: Progress: 100% (Rate: 2089k/s, Estimated time remaining: --:--:--)

==> default: Successfully added box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2' (v0.5.3) for 'virtualbox'!

==> default: Importing base box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2'...

==> default: Matching MAC address for NAT networking...

==> default: Checking if box 'mwrock/Windows2012R2' is up to date...

==> default: Setting the name of the VM: vagrantdemo_default_1474749910981_87953

==> default: Clearing any previously set forwarded ports...

==> default: Fixed port collision for 22 => 2222. Now on port 2200.

==> default: Clearing any previously set network interfaces...

==> default: Preparing network interfaces based on configuration...

default: Adapter 1: nat

==> default: Forwarding ports...

default: 5985 (guest) => 55985 (host) (adapter 1)

default: 5986 (guest) => 55986 (host) (adapter 1)

default: 22 (guest) => 2200 (host) (adapter 1)

==> default: Running 'pre-boot' VM customizations...

==> default: Booting VM...

==> default: Waiting for machine to boot. This may take a few minutes...

default: WinRM address: 127.0.0.1:55985

default: WinRM username: vagrant

default: WinRM execution_time_limit: PT2H

default: WinRM transport: negotiate

==> default: Machine booted and ready!

==> default: Checking for guest additions in VM...

==> default: Mounting shared folders...

default: /vagrant => C:/vagrantdemo

C:\vagrantdemo

λ

After the machine downloads, Vagrant will start the VM and run any provisioners defined in the configuration file (we haven’t configured any yet, so nothing will happen). If all goes to plan, your output should resemble what you see above.

You now have a running Windows Server 2012 R2 VM!

Poking around

Let’s explore our new server a bit. You should have a new VirtualBox window containing the server’s console, and under the project folder, there is a .vagrant folder.

Vagrant boxes all have a default credential with a username of vagrant and a password of vagrant. This box is no different. Feel free to log into the console and explore, but don’t make any changes just yet.

The .vagrant folder is a working directory where vagrant keeps track of things like the virtual machine name and various other metadata. This is all specific to your particular environment, and we don’t need to do anything with it. If you’re tracking your project in Git, you should add this folder to your .gitgnore file so that it doesn’t get checked in and synced down to other people’s machines.

At this point, you have two ways to log in. You can use the VirtulBox GUI, or you can use PowerShell remoting. Let’s stick with PowerShell Remoting.

Go back to your shell and ensure that you’re still inside of the directory you chose for your vagrant project. Type vagrant powershell and hit enter. You should see something that resembles the following:

C:\vagrantdemo

λ vagrant powershell

==> default: Detecting if a remote PowerShell connection can be made with the guest...

default: Creating powershell session to 127.0.0.1:55985

default: Username: vagrant

[127.0.0.1]: PS C:\Users\vagrant\Documents>

You’re now working inside of your VM.

Let’s check out c:\vagrant\. This is the project shared folder.

Run:

cd \vagrant

Get-ChildItem

Your output should look something like this:

Directory: C:\vagrant

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

d---- 9/24/2016 8:12 PM .vagrant

-a--- 9/24/2016 8:03 PM 3095 Vagrantfile

You can see the .vagrant hidden folder and the Vagrantfile. Anything written here will show up in the project directory and vice versa. This is where we can store scripts to call with our provisioner.

If you run Get-WindowsFeature it’ll list all server roles that can be installed. You’ll notice that the Web-Server role is not currently loaded. If we wanted to install it, all we would need to do would be to run Install-WindowsFeature Web-Server, but that would only install the web server in this instance of our VM. We want this to also be available to future runs, so let’s add that command to a script instead. Ensuring that you are still in c:\vagrant\ inside of the VM, run:

"Install-WindowsFeature Web-Server" > install-iis.ps1

This writes a new file install-iis.ps1 with Install-WindowsFeature Web-Server as the contents. Sure enough, if you check the directory listing, you’ll see that the PowerShell script now exists along side the other Vagrant files.

[127.0.0.1]: PS C:\vagrant> dir

Directory: C:\vagrant

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

d---- 9/24/2016 8:12 PM .vagrant

-a--- 9/24/2016 11:49 PM 50 install-iis.ps1

-a--- 9/24/2016 8:03 PM 3095 Vagrantfile

Type exit to return to the host OS.

Now that we are back in the host OS, let’s do a quick directory listing:

C:\vagrantdemo

λ dir

Directory: C:\vagrantdemo

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

d----- 9/24/2016 4:12 PM .vagrant

-a---- 9/24/2016 7:49 PM 50 install-iis.ps1

-a---- 9/24/2016 4:03 PM 3095 Vagrantfile

As expected, the new script, install-iis.ps1 now exists outside of the VM.

Provisioners

Vagrant supports provisioners that run against the VM after you vagrant up. They run the gamut from simple shell scripts to sophisticated configuration management tools like Ansible, Puppet and Chef. In addition to the built-in provisioners, Vagrant also supports custom provisioners that enable the use of technologies such as Microsoft’s Desired State Configuration.

In order to get the install-iis.ps1 script we just created to run when we vagrant up, we are going to use the script provisioner. Edit Vagrantfile in your favorite text editor. Insert the following line before the end statement:

config.vm.provision "shell", path: "install-iis.ps1", run: "once"

This configuration setting tells Vagrant to run install-iis.ps1, but only one time. This makes sense here, because we don’t want to attempt to install IIS every time the system boots.

The Vagrantfile, (excluding comments) should now look like this:

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "mwrock/Windows2012R2"

config.vm.provision "shell", path: "install-iis.ps1", run: "once"

end

Because the system has already been provisioned, simply rebooting won’t kick off the script. To run the provisioner, run:

vagrant provision

This forces the provisioner to run.

Tip: Running

vagrant provisioncan be a fantastic aid when you’re making incremental changes to a script and want to test along the way. If you pair it withvagrant snapshot(documentation here) to save and restore the state of the VM, it can be an incredibly powerful development tool.

With any luck, the command ran successfully, and you now have a functional web server installed. Your output should look something like this:

C:\vagrantdemo

λ vagrant provision

==> default: Running provisioner: shell...

default: Running: install-iis.ps1 as c:\tmp\vagrant-shell.ps1

==> default: Success Restart Needed Exit Code Feature Result

==> default:

==> default: ------- -------------- --------- --------------

==> default: True No Success {Common HTTP Features, Default Documen...

Port Forwarding

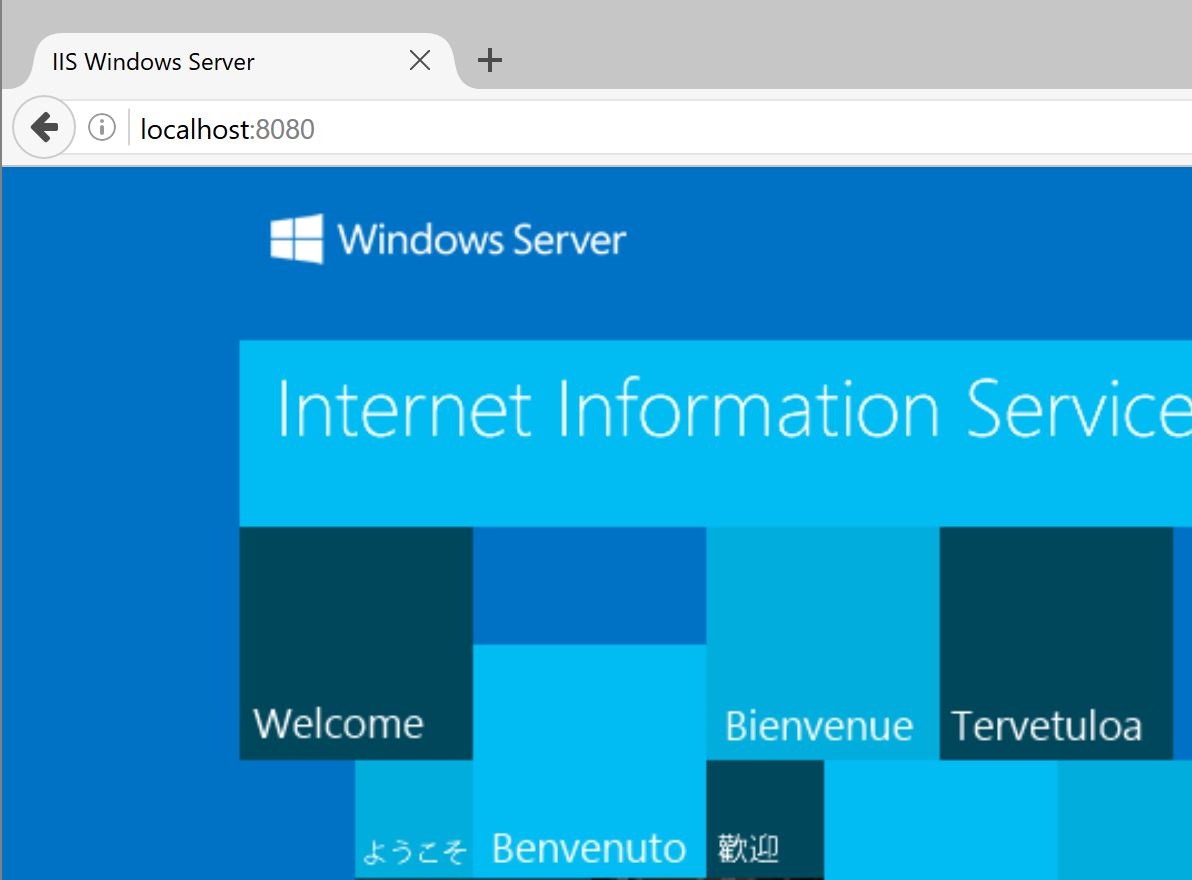

At this point, you have a functional web server. If you log into the windows desktop via VirtualBox, you can point your browser at http://localhost and get a page load. Unfortunately, you can’t load the page from your normal browser outside of the VM. Let’s fix that by adding one more line to the configuration file.

Once again, open Vagrantfile in your text editor. Add the following line above the provisoner line we added earlier:

config.vm.network :forwarded_port, guest: 80, host: 8080

This redirect port 8080 on the host to port 80 inside the VM. Excluding comments, your Vagrantfile should now look something like this:

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "mwrock/Windows2012R2"

config.vm.network :forwarded_port, guest: 80, host: 8080

config.vm.provision "shell", path: "install-iis.ps1", run: "once"

end

To enable the forwarder, shut down and restart the VM with the following commands:

vagrant halt

vagrant up

Once the machine boots, load up your browser of choice in the host OS and point to http://localhost:8080. With any luck, you should see the default IIS start page.

Vagrant Share

One last thing to try, is sharing your VM with remote users. You’ll need a free account on Atlas to do this, but it’s pretty cool. Run:

vagrant share --http 8080

This directs Vagrant to share our forwarded port (8080) as the HTTP port. Vagrant will give you a hostname that you can give to remote users so that they can visit the site. You can get the http URL from the output of the command:

C:\vagrantdemo

λ vagrant share --http 8080

==> default: Detecting network information for machine...

default: Local machine address: 127.0.0.1

default:

default: Note: With the local address (127.0.0.1), Vagrant Share can only

default: share any ports you have forwarded. Assign an IP or address to your

default: machine to expose all TCP ports. Consult the documentation

default: for your provider ('virtualbox') for more information.

default:

default: Local HTTP port: 8080

default: Local HTTPS port: disabled

default: Port: 2200

default: Port: 8080

default: Port: 55985

default: Port: 55986

==> default: Checking authentication and authorization...

==> default: Creating Vagrant Share session...

default: Share will be at: dreadful-armadillo-4080

==> default: Your Vagrant Share is running! Name: dreadful-armadillo-4080

==> default: URL: http://dreadful-armadillo-4080.vagrantshare.com

==> default:

==> default: You're sharing your Vagrant machine in "restricted" mode. This

==> default: means that only the ports listed above will be accessible by

==> default: other users (either via the web URL or using `vagrant connect`).

I visited http://dreadful-armadillo-4080.vagrantshare.com in my browser, and sure enough, IIS loaded for me.

Press control-c to terminate the share.

Note: Because Vagrant machines are intended for development use, they aren’t always fully patched, and often use insecure defaults. Please be mindful of this when sharing your Vagrant environment on the Internet. Also, please be aware that you’re sharing all forwarded ports, just the HTTP port. You’ve been warned.

Grand Finale

Good work! You’ve made it this far, now it’s time to delete the VM! Wait, what?! Don’t worry, because we built our configuration as code, the VM is ephemeral, and can be regenerated at will. Run:

vagrant destroy

It will ask if you’re sure, say yes. This will shut down and delete the VM. It will not however delete the box we used to create the VM from Vagrant’s image store. This is a good thing, as it won’t have to be re-downloaded when this or other Vagrant configurations that reference the image are spun up.

To regenerate the VM, just run:

vagrant up

Once the machine boots back up, test a page load to confirm that everything is working again.

One of the more amazing things about this, is that in order to share your environment with someone else, all you need to do is share the contents of your project folder (minus the .vagrant folder) and they can recreate the entire environment by just running vagrant up. In this case, that’s only two files, and the script that we wrote could easily be consolidated into the Vagrantfile so that we only had one file to share!

This really only scratches the surface, as you can perform very complex builds once you get into using the more advanced provisioners. You can even do multi-machine Vagrant projects! Another interesting option is to include a Vagrantfile with your existing projects. It’s just a single text file, but gives you a way to bundle an entire development environment with your work.

Examples

DNN Test Environment

At work, we use DNN as our Web content management system. I got tired of spending two hours building lab environments every time I wanted to tinker in a safe place, so I built an environment using Vagrant. One of the nice benefits was it gave me an opportunity to brush up on my PowerShell DSC, as it had been a while since I’d used it. You can find the project here. Now I can easily spin up fresh test machines whenever I want.

Blogging

This blog is hosted on GitHub Pages, and uses a Jekyll template called Beautiful Jekyll. The template came with a Vagrantfile that spins up a Debian image, installs all Ruby perquisites, and spins up the web server. This allows me to test changes locally, and I don’t have to go through the trouble of mucking up my laptop’s Ruby environment with all of the dependencies required to get Jekyll going.

Have you done anything interesting with Vagrant or have any ideas? Sound off in the comments!

Image courtesy of www.nasa.gov - http://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_2184.html